How do standards grow?

“It all starts with standards – they are at the heart of interoperability,” Canada’s Director of Digital Exchange Teresa D’Andrea concluded, as she summarized the government use case at the OMG’s Technical Meeting in Ottawa. But these must be highly consumable (take no more than 30 minutes for a technologist to understand) to drive usage. The OMG consortium has internalized this fundamental principle in its standards work through adoption of a models-driven approach. As Ed Seidewitz, CTO of OMG member company Model Driven Solutions, explained at the Ottawa session, “a model is recognizable. It faithfully represents some things, but not everything. By describing something under study, it promotes understanding, and specifies what needs to be built.” A modeling language, by extension, is a formal language for writing models, written as a set of statements that describe a system (for analysis), and describe requirements (for engineering). As examples, Seidewitz pointed to mathematics as the modeling language for scientific models, and programming language as the modeling language for computation. OMG’s mandate has been to develop standards for modeling languages as these provide “common understanding”: “its important to standardize,” he explained, “in order to communicate.”

OMG’s first standard – the Unified Modelling Language (UML) – was created in 1997 as the technical basis for designing and communicating distributed systems. Since then, OMG has developed specific profiles for UML based on different technical use cases, such as timing and integration and business processes. Ultimately, two families of standards have been created for the analysis, design and implementation of software-based systems, and for modeling business and similar processes. On the software side, these now include: SysML for Systems Engineering; MARTE for the Modeling and Analysis of Real Time Embedded Systems; SoaML, the Service Oriented Architecture Modeling Language, UAF, Unified Architecture Framework; fUML, the Foundational Subset for Executable UML Models, Alf, the Action Language for fuML, and PSCS, precise Semantics for UML. On the business front, the Business Process Model and Notation specification (BPMN), which is now also a recognized ISO standard, is a graphical notation for business processes that defines notation and semantics in diagrams for Process Orchestration and Choreography, Collaboration, Conversation (detailed messaging on how processes in choreography talk to each other). Other business process specifications include CMMN – Case Management Model and Notation (a common meta model and notation for modeling and graphically expressing a case) and DMN – Decision Model and Notation (describes how to make decisions to enable automation, and VDML (Value Definition Modeling Language).

Since this (abbreviated!) list of different technical and business process specifications fails the test of ‘easily consumable’, Seidewitz provided Ottawa Technical Meeting attendees with an example scenario – the use of UML business process framework to create an online shopping experience. He began with a schematic diagram outlining various functional processes needed to support the primary actor (the customer), and the relationships between bubbles representing the customer and secondary actors (vendor, authenticator, shipper) in the shopping process. Over this, Seidewitz overlay a UML activity diagram, shifting to a shopping system architecture using a composite structure diagram showing IT subsystems (components, such as search engine, management component, online shopping, authentication, customer management, order management, inventory management). As a next step, he defined the interfaces between components, and paths for communications via nodes to create a design. Using a sequence diagram that focuses on the lifelines – or messages that are passed between components – he was able to model the interaction between components, to complete the architecture. According to Seidewitz, “modeling helps you to find problems in your system – missing interfaces, for example – and you can check each use case scenario, and then validate the design (or potentially add in the missing interface!).” The Holy Grail, he noted in a systems engineering use case for optimizing vehicle manufacture, is to create a “system of systems” with traceability and plug in capabilities that allow designers to quickly check and modify system design.

Scaling standards efforts

As he outlined UML evolution, Seidewitz also discussed the process for setting research/work priorities in standards development. He explained that the OMG organizers rely on the community to decide what research is necessary next and he urged members to join one of these task forces – these would assess development efforts and assess needs, and then would issue an RFP inviting community members to come together to work on a specific industry issue. At the Ottawa Meeting, several OMG members presented on work completed in one or more areas through leverage of the models-based approach and use of one or more specification to solve for a new issue. For example, Nick Mansurov, CTO at KDM Analytics, reported on progress made by the Systems Assurance Task Force on development of the Model-based Cybersecurity Assessment. His talk focused on the use of MBCA with the Unified Architecture Framework (UAF) to identify, analyze, classify and understand cybersecurity threats – and how by plugging UAF into risk analysis, it is possible to automate the processes for repeatable security assessment.

In his presentation, Denis Gagné, CTO and CEO, Trisotech, described application of the OMG “Triple Crown,” the three complementary business process standards BPMN, CMMN and DMN to build continuous operational process improvement. Within the BPMN specification, he explained, each shape has one meaning, and because there is universal graphical notation for drawing business processes, a diagram can automate the creation of executable code, bridging the gap between modeling and subsequent action. A circle means an event, a rectangle is an activity, and a diamond is a gateway – which together can describe process sequence flow. According to Gagné, “It’s simple, but powerful because the business user can quickly understand the model – this flowcharting is an abstraction that is pretty natural and a good way to communicate with business,” who are the ultimate process owners.

Another business focused presentation was made by Claude Baudoin, principal consultant at cébe IT and Knowledge Management, who reported on preliminary definitions work that has been developed in two discussion papers published by the OMG Data Residency Working Group. The goal of this group is to create standard definitions of regulations in various jurisdictions and to define sensitive data so that tools can be developed that would better manage the movement of data from one location to another. Another aim is to establish process around data governance. Baudoin argued for establishment of a detailed governance structure, with clear roles and responsibility – “if everyone’s in charge, no one is in charge,” he added – as well as proper metadata management based on defined processes and rules on sensitive information. For his part, John Butler, principal at Auxillium Technology Group, discussed early efforts by the OMG Provenance and Pedigree Working Group, to establish standards for tracking and exchanging information that can identify the provenance of digital and physical artefacts, as well as their lineage (who touched the data during processing). This information will play an increasingly important role in the development of data trust, which applies across a range of applications, such as maritime safety (the working group’s original research area), supply chain, citations and fake news, electronic health records, records management, quality assurance and the use of test data. The group’s proposed Information model will include areas such as ownership of the data, custody, origin, transformation, and the identification of roles in the ecosystem.

Support for Canadian innovation

As the task force activities described above show, much of the OMG’s current group work is designed to support the creation of standards and best practices in information management. This is not surprising, given data growth in the last decade and our increasing focus on deriving value from information assets. In the data value proposition, sharing occupies a critical space – data that is stored in siloed repositories rarely delivers on its full potential benefit. But at the same time, data must be secured. In a session on Data Tagging and Labelling, Mike Abramson, CEO of the Advanced Systems Management Group, spoke to potential for conflict between open and secure data. Citing the former director of US National Intelligence James Clapper, Abramson pointed to “the need to find the sweet spot between sharing and protecting information. This paradox exists in every domain where sensitive information needs to be shared and used: in open data, open government, public safety, healthcare, and financial services.”

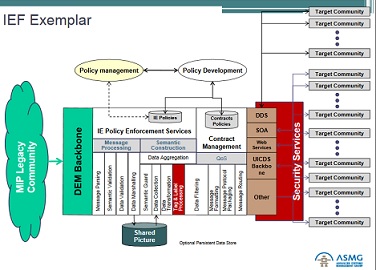

According to Abramson, the answer lies in “Responsible Information Sharing,” which maximizes sharing while simultaneously safeguarding sensitive data. The key, he argued, lies in metadata, in the creation of the Information Exchange Framework (IEF), which applies different types of contextual tags (descriptive, structural, administrative, provenance and pedigree, security, discovery, and handling instructions) to enforce policy around information sharing and security.

Advanced Systems Management Group’s work in this area began 25 years ago, and the firm’s engagement to help manage the sharing of NATO coalition data between US, the UK, and Turkey helped Abramson to recognize that “what you are willing to share,” in this kind of scenario, “is problematic.” Similarly, data transfer was challenging: “Originally, information managers were hardcoding their integrations, their APIs. But after six months, they had no idea what their interfaces were doing, and their interfaces never survived ‘first contact’ with the enemy. They had no way of updating them in a timely manner.” To enable information sharing, Abramson looked first for an existing interface application that would support integration. Since none existed, his team began to develop a modeling technique, a profile for UML to see if this could be used to generate interfaces. Their solution involved applying metadata in real time, ingest rules with data, and managing this in run time. To prove out this approach, Advanced Systems developed a technology demonstration for Public Safety and Security in Shared Services Canada, however, at that time no pilot mechanisms existed in the Canadian government, save for limited, specialized applications in the National Research Council.

Abramson’s team, however, was able to work on this broad interoperability challenge with the support of the OMG community. Led by Abramson, members in the OMG Command, Control, Communications, Collaboration and Intelligence Domain Task Force and the IEF Working Group have designed the IEF, a framework and reference architecture based on open standards for policy driven, data-centric and user-specific Information sharing and safeguarding (ISS), which delivers defence in depth to the data layer, responsible information sharing, delivery of the right/quality information to the right decision maker at the right time, and day-0 capability. The first IEF specification, the IEPPV, has also been published – a policy vocabulary and UML profile for secure packaging and processing of structured information elements. The IEF is platform independent – it may be implemented using one or more vendor products and services that can be integrated through standardized interfaces, messages and protocols. Abramson explained:

“In our metadata, the way we build the models, aggregate, and transform, we can mark in real time labelling and tagging of data. We can redact – we can pull out pieces that individuals can’t see. The recipient may be an individual, or a community of practice, a community of interest. We can control what information that goes to the community. If I’m using an IEPPV-type message, I have one definition of the message and it’s the content of the message that I’m controlling not the structure of the message. That’s where the innovation lies.” Furthermore, “we can control content to the individual recipient based on their authorizations and role, based on what the data owner determines is the risk. I separate the policies from the executable (a router or a database, for example) and manage them separately. Which means I can deploy my tech, and configure my tech for my mission.”

Since it is managed through policy, an IEF database can automate design-time ISS simulation and analytics assessments, triggering changes that might be required through out all associated elements. In addition, there is also an administrative interface that allows the user to go in and change and administer the policies. The result, according to Abramson, is increased flexibility, agility and adaptability on the information sharing front, as well as reduced cost and risk in information management overall. And because the IEF is model driven (not just code), users are able to retain institutional membership in the standards ecosystem to take advantage of new adaptations/and extensions going forward. “This technology is all Canadian innovation,” Abramson explained, modeled, polished and finalized with the help of the broader community.

The Advanced Systems Management Group experience highlights the key advantages of standards ecosystem development, as described by OMG CEO Richard Soley. While existing UML specifications helped the group replace a complex, point-to-point approach to API development with more readily accessible profile development of an existing specification, it has also simplified integration and data exchange for users, while introducing new safeguards for data. And by easing the development of best practices and standards, OMG is providing the supports needed to simplify and scale the innovation process itself. As Soley noted, the aim of the working groups is to identify “the new requirements for new standards that we can deliver … that will make it easier the next time a product/solution gets built. This is really about inventing the future, rather than waiting for the future to be upon us and disrupt our businesses.”