This post first appeared as a “cornerstone” chapter in Greener Data v.2. It represents a collaborative research effort, featuring input from several key thinkers on the need to develop a new kind of business case for sustainability, one that encompasses operational risk and social benefit.

It is reproduced here to mark Earth Day. To celebrate the day, and 20 years of marketing innovation, publishers of Greener Data v. 2, Jaymie Scotto and Associates, is offering a digital version of Greener Data v. 2 at a special, Earth Day discount rate. Your copy is here: https://lnkd.in/gY_ejv8E

————————————————————————————————-

Reconstructing the Business Case for Data Center Sustainability

A Greener Data Impact Report from Jaymie Scotto & Associates

Lead Analyst: Mary Allen, Sustainability Lead JSA and COO InsightaaS

Report Contributors: Peter Panfil, Vertiv; Francois Sterin, Data4; Michael Borron, Cushman & Wakefield; Peter Nisbet, Edenseven; Janie Blouin-Grondin, QScale; Eric Bouchard, QScale; Raymond Burrell, EkkoSense

Defining the ‘3P’ Business Case

Data center investment in the programs and technologies that improve environmental performance sway in response to market cycles, with the pendulum landing on ‘more’ in times of relative prosperity and ‘less’ when it’s time for belt tightening. Green IT was born in the decades of economic expansion leading up to the year 2000; sustainability discussions were quietly shelved in favor of ‘uptime’ and ‘reliability’ in the period of economic malaise that struck in 2007 and lingered to the middle of the next decade. And in recent years, the modest growth that bookmarked the pre- and post- Covid 19 periods, coupled with increasing climate consciousness, has fostered a resurgence of interest in data center sustainability. While these patterns may offer a rough calculus of the correlation between global economic trends and action on sustainability, they do underscore a common assumption that has served to justify varying levels of focus on sustainability in the data center world: when the economic climate allows an organization to invest appropriately, data center strategy expands to address the ‘twin ecos’ – ecological and economic benefits.

In this construct, the business case for sustainability is defined largely in financial terms. Aligning with conventional corporate mandates, the financial business case has inspired impressive momentum on sustainability, with innovation in the data center industry creating the efficiencies needed to balance out growth in sectoral carbon emissions associated with increased service demand.[1] Today, however, the swinging pendulum has come to a full stop, as traditional assumptions and models prove insufficient to master our current challenge – the need to reconcile industry growth and the demands of the looming climate crisis. Exponential increases in the data generated through the advance of digitization and rising global need for social, mobile, analytics and cloud services are driving unprecedented growth in the data center sector: measured by power consumed to feed in-house servers, data center demand in the US (which accounts for approximately 40% of the market) is forecast to grow at a rate of 10% per year from 2022 to 2030.[2] Along with investment in the sector by capital rich, non-traditional players, burgeoning demand is translating to a building boom: according to the Synergy Research Group, global spending on data center construction will achieve a CAGR of 5.4% over this same period.[3]

While mounting demand translates to significant opportunity for data center owners and investors, market pressure may also impact progress on sustainability. Today, vacancy rates for new data center sites are at an all-time low – 2.9% in the US – with development constrained by limited power availability and rising land costs, particularly in mature markets.[4] For operators looking to get to market quickly to capitalize on the emerging AI, IoT, and quantum revolutions, options are limited. With more demand than supply. operators will build where they can, with whatever energy grid is available, a response that will test plans for sustainable operation. Current market conditions could mean that widespread development of the ideal data center, built on high efficiency and clean power, will remain aspirational as power availability and time to market act as constraints on full blown sustainability.

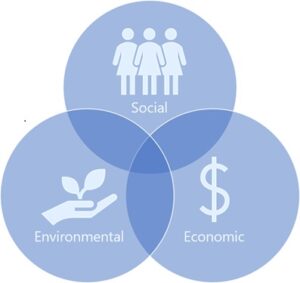

But what if other dynamics also play a role, and what if other issues can drive responsible data center development? What if new, more strategic thinking can replace transactional calculations to position data center activities in a broader context with longer term outlook? What business viability risks might arise if sustainability is not addressed – or how might the calculus change if the value in addressing ecosystem and community outreach is factored into the equation? Then we support data center growth with the “triple ecos” – ecology, economy, and ecosystem – an approach that parallels classical “3 P” definitions of sustainability, even as it works to ensure the long-term viability, the sustainability of the individual data center operation.

Figure 1. Triple bottom line 3 P’s: people, planet, prosperity

Parsing Sustainability Inputs and Outputs: Risk or Reward?

Defined as the methods and processes organizations use to manage risks that might impact achievement of its objectives, enterprise risk management (ERM) typically involves identifying events or circumstances that present threat or opportunity, assessing their likelihood and impact, and preparing a response strategy. The goal is to proactively address risk, in order to protect or create value for stakeholders. Sustainability risk management (SRM) is a subset of ERM, a growing discipline that recognizes the influence that sustainability inputs may have on the organization’s financial returns and long-term value. An effective SRM business strategy aims to align profit objectives with internal green plans and policies so that the business can grow while preserving the environment and addressing social and governance responsibilities (ESG).[5]

Risk will vary according to industry, location, markets, regulatory regime, and the organization’s objectives. In a data center context, there are several risk categories – events or circumstances that may present threat or opportunity – which can influence operational sustainability or even survivability. Categories of risk that can impact the data center, but which may be addressed through sustainability programming include resource scarcity, resilience, regulatory requirements, and corporate reputation.

Resource scarcity

The key risk factor for the data center is energy. Historically, land and location (proximity to markets and networks) informed data center site planning decisions. As latency concerns for most applications have faded with advances in communications infrastructure, access to power has emerged as the most significant constraint on industry growth. In many jurisdictions, owners/operators are seeing local restrictions on the connection of critical infrastructure to electric grid systems, ranging from directives requiring audits on energy use and data storage to outright permit refusals, or moratoria on construction of facilities beyond certain MW limits of IT load. Many markets are looking at mandating peak load shedding for new PPAs. As countries struggle to reach Net Zero carbon targets, the ongoing electrification of other industries will only drive further competition for resources – the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), for example, is expected to dramatically increase overall electricity consumption, as it introduces spikes in demand that can lead to blackouts in aging grid infrastructure. And in regions powered by clean energy, competition for resources is expected to intensify as data centers and other carbon-dense industries look for simple solutions to meeting environmental targets. For data center operators, ensuring access to reliable and adequate utility power looms as a business continuity threat, leading many to explore ‘bring your own power’ alternatives, including on-site sustainable energy generation and storage, in addition to the introduction of energy-saving systems and technologies.

Similarly, shrinking freshwater resources is urging caution on permitting, particularly in drought-stricken regions, by local authorities who must prioritize citizen needs; data center reliance on wasteful evaporative or open loop cooling techniques is shifting operator preferences for locations in watersheds that are under less stress or towards new tactics like greater use of free air cooling.[6] Data centers are also subject to resource risk resulting from supply chain failure – semiconductor shortages during the Covid 19 pandemic, is a familiar example, or from the scarcity of raw materials, such as copper, which represents a rising risk. Copper is a critical component in networking, heat exchange, and electrical infrastructure – approximately 27 tons of copper are needed per MW of applied power in data centers[7] – however, market experts predict a supply shortfall due to electrification by the next decade.[8]

Resilience

In the data center, rule number one is ‘no failure.’ A data center outage may result in compromise of service level agreements with tenants, triggering delivery failure to their clients, setting off a cascade of financial loss and reduced trust. Increasingly, risk mitigation plans are factoring in the impact of climate change on resilience, with organizations developing adaptation strategies that extend beyond financial loss to ask, “what does it mean to live with accelerating climate change?” In the data center, this adaptation planning may encompass new siting criteria, response to increased outages due to severe weather events or supply chain disruption, new relationships with insurers, or even the need to account for higher outside temperatures with additional cooling – in addition to water and power scarcity. Plans to mitigate these risks are an increasingly important factor in client retention, in the case of large customers in particular who sign multi-year contracts that call for assurance of the provider’s viability in the face of climate risk.

Regulatory

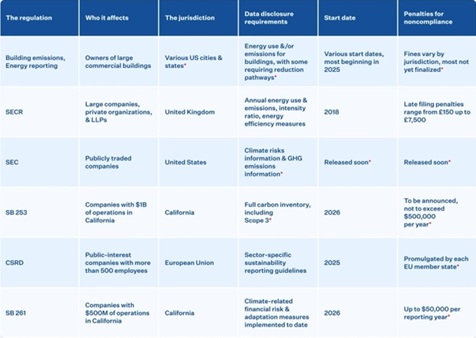

Environmental regulation of data center operation varies from region to region, with jurisdictions in the Asia-Pacific region, such as Singapore, leading on ESG disclosures, and the Nordics and Europe also setting standards. In the EU, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, the EU Code of Conduct for Data Centers, the European Energy Efficiency Directive and the EN 50600 regulations require reporting on energy consumption and carbon emissions, as well as concrete energy reduction plans to drive progress on sustainability goals, such as replacement of backup diesel generators. North America lags behind, though observers expect that a financially driven SEC proposal for a climate disclosure rule to improve the quality of company reported ESG data may soon translate to reporting with more bite in the US. But like most large organizations today, data centers do not operate in isolation; they service clients across continents and may be part of large global fleets – and so are required to comply with regulation in the particular country in which they operate. According to the Uptime Institute, approximately 63% of operators globally believe the authorities in their region will require public reporting of environmental data in the next five years – even though today, just 37% collect carbon emissions data, and 39% report their water usage.[9] Fines for failure to comply can be significant: the recently passed German Energy Efficiency Act mandates that data centers report on environmental metrics, implement an energy saving system, introduce a specified share of renewable energy, engage in energy reuse, and achieve a set PUE value in operations. Maximum fines for non-compliance range from €50,000 to €100,000, depending on the violation.[10]

Figure 2. The cost of noncompliance

Reputation

Lambasted by the media as key contributor to climate change and viewed by regional authorities as a drain on water/energy resources that generates little local employment, the data center industry faces an uphill battle in efforts to rehabilitate its reputation. Many large-scale facilities have taken up the challenge on the sustainability front, investing in environmental systems and clean energy solutions in efforts to position as climate leaders. For the hyperscale data center provider, sustainability has become a market differentiator that builds brand acceptance, employee enthusiasm, and client lists as customers work to improve their own environmental profiles. Compliance with regulatory requirements, transparency, and voluntary reporting are key tactics that can transform this risk to opportunity, which will be missed by data centers that are perceived to be wasteful of resources.

Figure 3. 4 R categories of data center risk

Reconstructing the Financial Case

When neglected, these risk factors can impact the longer-term profitability and viability of the data center operation. But when sustainability initiatives aimed at mitigating risk are viewed through the lens of quarterly or annual results, questions emerge. What is involved in creating the uplift needed to adopt the technologies, processes, and training that can help the data center identify and achieve sustainability goals? How much training is needed, what are the costs, and how will the introduction of green programs affect productivity?

Depending on current state and the company’s goals, answers to these questions can be complex. In cases where the existing facility is old or located in an area with high power or occupancy costs, a decision may be made to build new with state-of-the art systems, high efficiency infrastructure, and more green material components, though these strategies and technologies can be very capital intensive and take years to implement. In most instances, a useful tactic to kick start sustainable programming is to identify the ‘low hanging fruit’ – new approaches, technologies, or processes that deliver quick financial returns, inspiring an appetite for more work. Examples would include repurposing existing office or industrial buildings rather than construct new data center sites, or increasing the temperature in data rooms, a tactic that requires no investment, but pays back in reduced cooling expense. Similarly, use of free air cooling or hot/cold aisle containment involves little capital outlay. In some jurisdictions, such as Quebec, Canada, power from renewable energy resources is actually cheaper than electricity from fossil-fuel generation. Each of these tactics yield savings on cost and carbon.

Since 2014, energy improvements won through low hanging fruit have stalled, with PUE hovering at approximately 1.55[11] in subsequent years. This stasis has called for more sophisticated approaches to driving improvements. A second key principle is to optimize existing assets before introducing new capital projects. For example, rescuing stranded assets from server, power, and thermal perspectives can introduce significant savings on items such as power expenditure. As these represent fixed costs that operators are resigned to spend, savings represent pure margin. Similarly, the deployment of systems and components with advanced energy efficiency capabilities can reduce losses – typically by a factor of two – producing savings that contribute to helpful total cost of ownership (TCO) calculations. With TCO, upfront investments in sustainability solutions may be amortized over time through power savings, rendering expense net neutral. At the same time, TCO methodologies allow operators to better balance progress towards multiple goals: zero carbon, zero waste, zero losses, and zero water.[12]

As high efficiency technologies reduce cooling requirements, they enable the deployment of additional compute infrastructure in existing space. For the colocation provider, this may translate to signing additional two- or three-year leases. For the owner/operator, it may mean accessing additional capacity minus the financial costs associated with new build – and the Scope 3 emissions that come with deploying new concrete, cabling, and other facilities infrastructure. Moving beyond a ‘cost first mentality’, this lifecycle perspective considers cost and benefits over time, as well as the interplay of different data center inputs to reduce waste, helping the operator realize the opportunity in sustainability as it evolves over generations of technology and business leadership.

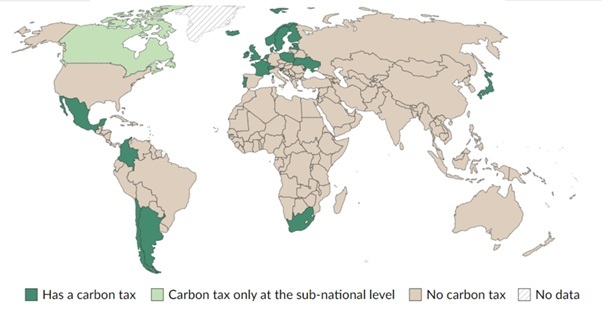

Placing data center operations within a broader sustainability context introduces an additional financial calculation. While not ubiquitous, a carbon levy on GHG emissions is now applied in multiple jurisdictions, with more likely to adopt this approach going forward. In these regions, goods and services that emit more carbon in production will pay a higher tax; when carbon pricing is included in data center lifecycle costs, the operator will arrive at an environmental-inclusive ‘TCO2‘ that can inform future-facing business decisions. Carbon taxes vary from market to market, with some jurisdictions pricing carbon high enough to incent investment in sustainability measures, including the establishment of programs that specify preference for suppliers with low emissions and a verifiable environmental footprint. In the race to Net Zero by 2030, a more advanced data center provider that establishes the value in carbon savings can demonstrate more progress on sustainability goals, offering a compelling option for customers looking to deliver on their own sustainability KPIs, and creating for itself a revenue-based business case for carbon accounting.

Figure 4. Which countries have a carbon tax? 2022

Building Social License

At a macro level, the data center sector is in an excellent position today. Demand for data services is at an all-time high, vacancy rates are low, non-traditional investors are entering the market to capitalize on growth potential, and technology innovation has enabled ever-expanding capability to support increasingly sophisticated applications that can solve real world problems. But is this the view held by the communities that data centers reside in? With unprecedented growth – a 100 MW facility is no longer interesting to many operators, as PUE improvements are becoming more elusive – an alternate perspective on data center value is gathering strength. In many communities, the sought-after development opportunity is now superseded by a vision of the data center as a competitor for scarce resources, including energy, land, and water, which operates in a secretive way, offering little local employment but causing negative impact on air quality and local biodiversity. This emerging analysis is affecting the welcome data centers receive from local municipalities who can withhold permitting for new build or from regional utility providers who may impose supply limits in contractual agreements. As the effects of climate change and competition for resources intensifies, this divergence is likely to grow apace.

In this context, how can the data center industry recover its image as a good, contributing corporate citizen? How can the data center create the social license that is a precondition to continued growth? The answer lies in community outreach across a variety of stakeholder groups, greater transparency and governance to build trust, and repositioning as a long-term contributor, rather than enemy of social and environmental sustainability.

Empowering the utilities

Fulfilling the energy needs of power-hungry data centers has become very challenging for many utility providers. Beyond overall consumption requirements, which can be significant in the case of larger facilities, data centers can threaten the stability of the grid. If, for example, the data center chose to remove significant load at the same time, voltages, frequencies, and heat would jump. Utilities are designed to work in steady state conditions with customer continuity; grid updates needed to address key requirements, such as managing demand fluctuation or the integration of distributed energy, are beyond the reach of many suppliers. To reduce pressure on the grid, data centers can engage in a number of activities, such as contracting long term power purchase agreements for clean energy (helps decarbonize the grid), they can improve energy efficiency, powering at least part of the campus through onsite renewable generation, or they can build partnerships with the local utility to enable grid interactivity and support grid resilience.[13]

Waste not; want not

A key sustainability tactic is to reduce waste; in the data center, an economic but effective way to demonstrate commitment to sustainability and the local community is to deliver heat waste to local systems. This typically takes the form of transferring heating to adjacent office structures, but may involve the exchange of heat waste to district heating systems. In Paris, a popular approach is to heat swimming pools, while in Canada, data center provider QScale is leveraging its liquid cooling solution to maximize heat recovery and send excess heat to green houses in its rural vicinity, a priority for government that is looking to support the agricultural sector as it greens its operations. Going forward, finding opportunities for data centers to collocate with utilities and district energy providers may influence siting decisions, as the industry works to secure energy contracts with the utility: doubling the benefit of a single electron can be an attractive proposition for the sustainable data center, the municipality, and the local energy supplier.

Supply chain development

Heat reuse projects are not built in a day; they are built over a period of years and require that the data center, utility, integrators, and other specialist industries work together to benefit the broader community. Locating the data center within vacant commercial or industrial space and converting this for use as a district energy hub, for example, may help data centers deliver on their economic development promise as they help develop the skills, templates, and systems needed for implementation of this kind of sustainability project. But contributing to the construction of a healthy, sustainable supply chain is not limited to heat reuse. For example, there is an emerging use case for hydrogen fuel cells in data center backup power, which can replace dirty diesel backup generation, as it bolsters a nascent green industry solution. A municipality interested in green construction jobs or clean energy startups might count this type of innovation as a significant benefit that may be gained through a sustainable data center build.

Education

Knowledge sharing by the data center can work on several fronts to develop community acceptance. Collaboration on sustainable operations can raise awareness as it inspires greater action among industry peers. For example, through engagement with national industry associations and global working groups, a provider such as Data4 aims to de-risk innovation, driving progress on sustainability that can lift the profile of the entire industry in terms of environmental performance. Data4 has also created partnerships with local educational institutions to help prepare students for jobs of the future; QScale works with a local university to explore new use cases and optimal locations for heat recovery projects. Public education may involve opening up the facility to visitors and helping the public better understand the vital role that digital infrastructure plays in creating social and economic value.

Campus design

Designed for maximum security, the typical data center has loomed fortress like, built with anonymous and impenetrable concrete structures. But it is possible to lift this veil on data center operation, which has served to create suspicion. Improvements to latency and the current trend towards construction of larger facilities that can service future demand have pushed many data centers to locate in rural or suburban sites with considerable acreage. Parks can be created from excess land to welcome the public, and community amenities built onsite to support visitors, such as EV charging stations, or small transit systems to transport guests across large campuses.

These activities – working with utilities, peer groups and associations, supply chains, local innovation ecosystems and educational institutions, and structuring the data center campus to better host guests – can help to revitalize the data center image. In establishing the data center as a good corporate citizen that contributes to community health, environmental performance is a prime mover. Whether it’s helping to improve grid stability, reducing demand on resources, innovating to improve efficiencies in data center or district systems, or educating to drive further understanding of strides the industry has made to reduce carbon impact, sustainability serves as the critical input that can convince the community to engage.

Imagine

Imagine a ‘Geoexchange’ – a geothermal closed loop water system that acts as a utility to transfer heat across different applications. Throughout this loop sit a series of highly efficient modular data centers that operate close to Net Zero carbon, and contribute heat to other systems – a greenhouse, a swimming pool, sustainable housing, a research center with multiple campus structures, various business services, even a lobster farm – or for storage in the earth. In this distributed resource model, interactions and transactions are made in the community, close to the point of use. Based on the digitization of services, this system is reliant on the data center which provides heat and manages interactions and no longer requires social license as it is fully integrated into the community. The outside of the system is planted with vegetation, and the whole treated as a shared responsibility and shared resource. Imagine a way of living powered by the data center that aligns with sustainability principles. We have the technology and the business case – all that is missing is the will.

Mary Allen is COO at InsightaaS and Sustainability Lead for JSA. As journalist, analyst, and content strategist, she has covered the range of IT subjects for her own properties, and on behalf of clients. Mary created the GreenerIT and Sustainability Platform websites, capping this with a stint as sustainability columnist for Bloomberg BNA, to promote the environmental agenda within IT. She continues this passion in partnership with JSA on the Greener Data initiative.

Mary Allen is COO at InsightaaS and Sustainability Lead for JSA. As journalist, analyst, and content strategist, she has covered the range of IT subjects for her own properties, and on behalf of clients. Mary created the GreenerIT and Sustainability Platform websites, capping this with a stint as sustainability columnist for Bloomberg BNA, to promote the environmental agenda within IT. She continues this passion in partnership with JSA on the Greener Data initiative.

Peter Panfil is  a recognized veteran of the power industry. For over thirty years, he has held executive positions with key power systems vendors, including Liebert, AC Power, and now Vertiv, and is a frequent presenter on power and cooling issues and opportunities in the mission critical space. As VP Global Power at Vertiv, Peter now leads customer development, helping clients deploy solutions to enhance the availability, scalability, efficiency, and sustainability of their infrastructure.

a recognized veteran of the power industry. For over thirty years, he has held executive positions with key power systems vendors, including Liebert, AC Power, and now Vertiv, and is a frequent presenter on power and cooling issues and opportunities in the mission critical space. As VP Global Power at Vertiv, Peter now leads customer development, helping clients deploy solutions to enhance the availability, scalability, efficiency, and sustainability of their infrastructure.

Francois Sterin has extensive experience working in key infrastructure areas, ranging from backbone network to content distribution, data center, and energy. He has held executive roles in these critical areas for program delivery across all continents, and with major hyperscale operations including Google, OVHcloud, and France Telecom. As COO for Data4, Francois is now focused on helping the European operator build out a scalable and sustainable platform to support today’s rapid growth of digital infrastructure.

Francois Sterin has extensive experience working in key infrastructure areas, ranging from backbone network to content distribution, data center, and energy. He has held executive roles in these critical areas for program delivery across all continents, and with major hyperscale operations including Google, OVHcloud, and France Telecom. As COO for Data4, Francois is now focused on helping the European operator build out a scalable and sustainable platform to support today’s rapid growth of digital infrastructure.

Pete Nisbet is the Managing Partner at edenseven ltd a sustainability consultancy (part of the Cambridge Management Consulting Group), who support businesses in developing and delivering net zero strategies. Pete started his career working for SSE (a UK based Utility Company) within their operations team and since then has built a deep understanding of the Energy and Carbon sector having held senior roles in operations, commodity trading and portfolio management. Prior to joining edenseven, Pete was Managing Director for Mitie Energy (the UK’s largest Facilities Management Business).

Pete Nisbet is the Managing Partner at edenseven ltd a sustainability consultancy (part of the Cambridge Management Consulting Group), who support businesses in developing and delivering net zero strategies. Pete started his career working for SSE (a UK based Utility Company) within their operations team and since then has built a deep understanding of the Energy and Carbon sector having held senior roles in operations, commodity trading and portfolio management. Prior to joining edenseven, Pete was Managing Director for Mitie Energy (the UK’s largest Facilities Management Business).

Janie Blouin-Grondin, CPA and MBA, is a strategic thinker who works to apply quantitative analysis and analytic skills to organizational challenges. She has worked as project manager and as business transformation advisor for clients at Desjardins Insurance Group and Edgenda. Janie is now Director of Strategic Initiatives and Corporate Operations at QScale, a provider of high-performance computing centers with built in heat recovery.

Janie Blouin-Grondin, CPA and MBA, is a strategic thinker who works to apply quantitative analysis and analytic skills to organizational challenges. She has worked as project manager and as business transformation advisor for clients at Desjardins Insurance Group and Edgenda. Janie is now Director of Strategic Initiatives and Corporate Operations at QScale, a provider of high-performance computing centers with built in heat recovery.

Eric Bouchard is a tech exec who combines technical and marketing perspectives as he leads product design teams from concept to launch. He has developed expertise on customer experience, new revenue models, user research and competitive analysis in positions at Coveo, Mirego, and Copernic QScale, and now brings these skills to QScale.

Eric Bouchard is a tech exec who combines technical and marketing perspectives as he leads product design teams from concept to launch. He has developed expertise on customer experience, new revenue models, user research and competitive analysis in positions at Coveo, Mirego, and Copernic QScale, and now brings these skills to QScale.

Michael Borron is a Broker and Associate Vice President within Cushman & Wakefield’s Global Data Center Advisory Group. He speaks frequently about sustainability in data center site selection, and works with clients to help prepare and structure acquisitions today for a near future in which sustainability means competitive advantage.

Michael Borron is a Broker and Associate Vice President within Cushman & Wakefield’s Global Data Center Advisory Group. He speaks frequently about sustainability in data center site selection, and works with clients to help prepare and structure acquisitions today for a near future in which sustainability means competitive advantage.

Dean Boyle co-founded EkkoSense, a global SaaS company that helps data center teams looking to boost operational performance. EkkoSense has a mission to resolve the thermal risks due to insufficient cooling. As CEO, he has driven the company to its current position as a leading provider of AI-based optimization to reduce data center cooling cost and support clients ESG programs.

Dean Boyle co-founded EkkoSense, a global SaaS company that helps data center teams looking to boost operational performance. EkkoSense has a mission to resolve the thermal risks due to insufficient cooling. As CEO, he has driven the company to its current position as a leading provider of AI-based optimization to reduce data center cooling cost and support clients ESG programs.

Notes:

[1] Over the past several decades, IT and facilities innovation has kept sectoral GHG emissions at approximately two percent of global totals.

Eric Masanet, Arman Shehabi, Nuoa Lei, Sarah Smith and Jonathan Koomey. “Recalibrating global data center energy-use estimates.” Science, vol. 367, no. 6481.

[2] Srini Bangalore, Arjita Bhan, Andrea Del Miglio, Pankaj Sachdeva, Vijay Sarma, Raman Sharma, and Bhargs Srivathsan. “Investing in the rising data center economy”. McKinsey & Company. January 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jacob Albers. Americas Data Center Update: October 2023. Cushman & Wakefield. October 2023.

[5] L. Zu. Sustainability Risk Management. Idowu, S.O., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., Gupta, A.D. (eds) Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28036-8_257

[6] Michael Copley. Data Centers, backbone of the digital economy, face water scarcity and climate risk. NPR. August 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/08/30/1119938708/data-centers-backbone-of-the-digital-economy-face-water-scarcity-and-climate-ris

[7] Bruno Venditti. Copper: The Critical Mineral Powering Data Centers. Visual Capitalist. November 2023. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/sp/copper-the-critical-mineral-powering-data-centers/

[8] Yusuf Khan. Copper Shortage Threatens Green Transition. WSJ Sustainable Business. April 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/copper-shortage-threatens-green-transition-620df1e5

[9] 12th Annual Global Data Center Survey. Uptime Institute. 2022. https://uptimeinstitute.com/about-ui/press-releases/2022-global-data-center-survey-reveals-strong-industry-growth

[10] Dentons. How Germany’s Energy Efficiency Act will impact data center operators. October 2023.

[11] Uptime Global Data Center Survey.

[12] In the past, a favored approach to reducing PUE was use of large, evaporative cooling systems, which consume enormous amounts of water.

[13] For more on data center support for utilities and grid interactivity, see “Low Carbon Solutions: Pathways to Energy Maturity in the Data Center,” in Greener Data, v. 2. JSA. April 2024.