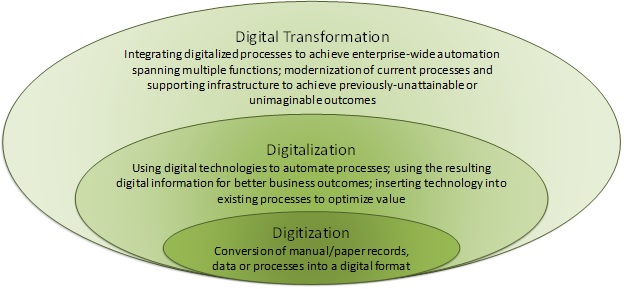

Digitization is the new BPM, jet fuelled by the latest technologies that automate to optimize business processes. It is what managers are now told is critical to maintaining competitive edge; in a business landscape populated by competitors who have embraced the digital imperative, it is key to survival, so goes the new narrative. But haven’t organizations been digitizing for decades? The short answer is ‘yes’. While email and text effectively displaced paper communications a quarter century ago, ecommerce followed closely on the heels of the Internet’s public launch in 1991, and computerized management in the manufacturing world began to take hold back in the 1950s. But the longer answer, reflecting the complexity of broad-scale change, is more involved. Today, the pace and the scope of going digital has unleashed a new business phenomenon, and an ambitious change agenda has established a new goalpost – complete transformation of the enterprise. Some of the complexity involved in this transition is outlined in the conceptual framework presented below.

Developed by Techaisle Research, this framework details staged progress towards digital transformation: digitization converts manual processes into digital formats; digitalization technologies automate processes to optimize value; and at the transformational stage, digitalization works enterprise-wide to achieve new, and sometimes, unanticipated business outcomes. As with any modernization journey, the road to digital transformation can follow many paths; however, the new accelerated pace of digitalization lends much to the marriage of new and older approaches to software update, specifically, the application of new digital technologies to BPO by a new cadre of application innovators. Today, growing interest and demand for these “transformational technologies” is creating unique opportunity for software providers, enlivening markets on a global basis, but especially in key tech hotspots, including cities such as Toronto and Montreal.

The WorkJam vision

Tech developments in Montreal’s retail environment provide case-based insight into this progress of digital evolution, and the WorkJam example offers unique view into the development of a new software platform that enables the digitization of communications processes. CEO and co-founder of company Steve Kramer is a Montreal native who worked initially with his father, Irwin Kramer, in the family business – Richter Systems, a provider of specialized commercial software targeted at large retailers and distributors that was established in 1968. Along with partner Joshua Ostrega, in 1999 Steve Kramer launched a new company, iCongo, a software vendor of omni-channel retail and B2B commerce solutions, which merged with the UK-based Hybris Software in 2011. Soon after, the combined entity became the largest independent provider of ecommerce solutions, with 300 employees in Montreal, 1,200 on a global basis, and offices in 23 countries to support 600 customers. In 2013, Hybris was sold to SAP.

In his decade long experience at iCongo/Hybris, Kramer focused largely on educating the market about notions of customer experience: how do you create a seamless experience for the customer that spans a browse of the website, a visit to the store, and completing a mobile transaction the next day? But when deploying the technology into retailers’ stores, the Hybris team was able to identify a new opportunity around human processes: “we realized there was very little innovation or investment in enhancing the store experience by investing in people,” Kramer noted. “How do you train them, how do you communicate with them, how do you get alignment between what corporate is looking to do and what workers on the floor are saying,” are areas that Kramer believed could benefit from automation. “You could go into one of the largest retailers, where there was a ton of expensive technology and still find that the company was communicating with workers via a bulletin board in the back,” he explained. “There would be very manual communication and text messaging – managers would put in their own communications tools because it was so out of control.” The vision behind WorkJam was to enhance the store experience by focusing on the “last mile” – bringing the concepts of ecommerce to workforce management.

With former iCongo execs Joshua Ostrega and Mark Sadegursky, Kramer launched WorkJam four years back – a digital workplace platform that provides a mobile and web solution for associates working in retail stores or for other employees in large organizations, such as nurses in a hospital, or floor workers in a logistics centre. The platform ties together data sets that exist in back office systems, such as schedulers, learning management content, and sales data, into one application that enables better dissemination of information out into the field. Information is shared in a timely and digestible manner, and as Kramer argued, in a way that increases productivity and cuts costs for the organization.

A corporate initiative, WorkJam works by helping staff achieve maximum productivity through the digitalization of workforce communications. A key platform capability is self-scheduling via a corporate portal that offers the employee maximum flexibility and hence job satisfaction. And though some WorkJam customers have proved reluctant “to turn over the keys to the car,” Kramer explained that “what we really sell is the ability to manage all the transactional elements around this.” To illustrate, he compared old process – where a sick employee would text the manager and he/she would have to individually phone or text replacement workers – to the ability to broadcast an open shift broadly across the organization through the WorkJam platform, and thereby save management time. “It’s not about loss of control,” he added, rather its about delivering information around cancelled requests, call ops, shift trading, and schedule presentation in a way that leads to better productivity, which ultimately benefits the employer.

Another area in which WorkJam enables HR innovation is education. Today, many companies deliver employee training on a location by location basis. But with the WorkJam platform, organizations can begin to think differently about resources, pooling labour resources within a district or region to provide more work for people, which in turn reduces training and labour costs. According to Kramer, labour is typically the highest cost item in an organization’s budget: on average, it costs a retailer four to five thousand dollars to recruit and train a new employee. So a tool like WorkJam, which reduces attrition by providing more flexibility and predictability in scheduling, more self service and some lifestyle scheduling, can have a massive impact on a large company’s bottom line – in the tens of millions of dollars for some organizations. Training via mobile devices also increases the effectiveness of training – for example, when a company has to ramp up staff numbers for seasonal work, savings can be significant. One WorkJam warehouse client was reportedly able to save $12 million per year by streamlining the onboard process.

A key characteristic of digital transformation (as outlined above) is broad deployment of digital technologies across the organization. To support enterprise orchestration of digital assets, WorkJam integrates with key corporate systems, such as HR, and has commercialized these integrations. Many retail companies use the Kronos workforce management system – WorkJam has developed an out of the box integration that links to its back office scheduling tool. These integrations are helpful as they can save time for IT; however, even more important from a content perspective, is integration with back office systems that contain the organization’s business rules. Other integrations exist for Form, which Kramer called the EDI of training, to support the leverage of training assets the client already has, as well as for JBA, PeopleSoft, SuccessFactors and the larger enterprise learning management systems.

In Kramer’s view, most of the real work in the implementation comes with change management. To derive maximum benefit from the WorkJam software, the organization will have to develop an approach that is global, more consumable, and which in some cases, will involve the reengineering of existing processes. To support clients on this journey, WorkJam has developed relationships with implementation partners with process expertise, such as Axiom Workforce Managmement Consulting, Deloitte and Accenture.

Summing up the WorkJam impact, Kramer observed: “Many of our customers are undergoing large transformation in their businesses; with new competitive forces in the marketplace like Amazon, they are having to reinvent themselves. This is hard if you don’t have a way to communicate effectively down to the field. It’s become mission critical for a lot of organizations to put our solution into place – not only to protect margins and increase revenue, but really to survive. To transform, as many industries are finding they have to….”.

Kramer’s message is apparently resonating with the market. Since launch, the company has experienced significant growth: it now has a second office in Cincinnati, 85 employees, and includes many of the iconic retail brands (Macy’s, Shell Retail, Target) with large numbers of workers (20,000 to several hundred thousand) on its customer list.

Canada as a success incubator

Kramer attributes much of WorkJam’s success, and the success of other local tech businesses to the support provided to the startup community by Canadian governments. In addition to grants from Revenue Canada and provincial agencies, he also pointed to the “phenomenal technical labour force” and an educational system which “is so well tailored to educating people on technology and on entrepreneurship” that has been created in many Canadian cities. He contrasted this with the highly mobile workforce that exists in other global regions: “there is less mobility, especially in Quebec because of the language, so people don’t move as readily as they might in the US,” he observed.

For generations of Kramers, Montreal has served as a nurturing locale to launch a business. “It’s a great landscape to start a company,” Kramer added, that has become very competitive over the last couple of years as a centre for artificial intelligence, fuelled by programs at Université de Montreal and Concordia University. But WorkJam has also benefited from the city’s characteristic market focus: “Montreal has always been a hotbed for retail technology [going back to Irwin Kramer’s firm],” he explained. “Over the past 20 years, there have been several success stories in this area, based on the predominance of the clothing industry in the city that stretches back 25 years.”

Beyond an educated workforce and government sponsorship, funding to support commercialization of product/service innovation is often critical to a new organization’s success – support that has historically been less forthcoming in the Canadian tech environment than it has been in places such as Silicon Valley. With proceeds from the SAP Hybrid acquisition, WorkJam founders were in a position to funding the startup on their own. They chose instead, however, to access VC funding, to work with partners that could add value from a business development perspective, who could accelerate the sales cycle and the creation of relationships that the company would need to build. Kramer stressed the importance of connecting early with a “financial ecosystem.” “With iCongo, it took us 15 years to get from inception to the SAP acquisition, but the world runs so much more quickly these days. We felt it was really important to be able to tap into the financial ecosystem through a VC firm, because if we were to do another round, they have relationships that we don’t have, and as leading venture capital firms, they lend a certain level of credibility.”

Kramer cites government funding (for example, the SR&ED program the Canadian government provides for R&D in the form of reimbursements for development costs) as being instrumental to AI or technology development in general, which provides a huge advantage to Canadian businesses in terms of keeping costs down, and in terms of job creation. However, he also pointed to significant private equity and venture activity in Montreal and Toronto. Along with a few other AI companies that have attracted leading equity firms, Element AI, for example, managed to raise a hundred million dollars from Microsoft and Intel and other venture firms.

Funding support, an educated workforce, local success story models and the creation of multiple domestic incubators/accelerators, has spawned a new level of confidence and expectation on the part of Canadian entrepreneurs. As Kramer noted, six or seven years ago, the average exit for a technology firm in Montreal was probably around $5-10 million. But today, Canadian companies are able to attract significant valuations/dollars from US and foreign-based equity firms. iCongo, for example, sold for US$1.4 billion. “There’s a growing appreciation within these organizations for what’s happening in Montreal – there’s a lot more activity than we saw even three to four years ago around funds that are investing in Canada, as well as Canadian funds that have created growth equity funds to get in on the game as well.” Larger pension funds and larger equity firms that have traditionally focused on manufacturing or distribution are creating growth equity funds to get in on the technology segment, he explained, “And they’re writing sizable cheques.”