A common critique of regulation aimed at protecting citizens is that technology moves more quickly than policy makers. Given the rapid pace of innovation in IT, this argument has much merit: it is likely, for example, that new tools for monitoring and surveillance are in the market before creators or regulators have had a chance to consider how or if informed consent could be applied to ensure protection of privacy. Part of this lag can be attributed to a lack of resources at the policy level, but another requirement is for industry to consider the social implications of technology advance. In the rough and stumble towards profit and productivity, however, this kind of analysis is rarely on the table for producers of technology or for traditional IT research firms.

In a two part research series, The 451 Research Group has broken out of this mold with an exploration into the impact of advanced technology on the labour market. Beginning with the Industrial Revolution in part 1 which follows below, Owen Rogers, Nick Patience and William Fellows weigh short term job losses against overall productivity gains, arguing that technology innovation typically carries with it new opportunity – at least for those who are able to transition through reskilling. But is it “as simple as that”? To learn more about the mechanics of this transition – who benefits and who does not – read on. And stay tuned for part 2 in which 451 research tackles issues around AI and its impact on the white collar, professional workforce. (ed.)

From autonomous cars to cancer detection, computers are increasingly matching human performance, not just on manual tasks but cognitive ones, too. In this report, we discuss whether the labor market has benefited from improved technology. In a follow-up report, we discuss the impact that artificial intelligence (AI) will likely have on the labor market.

The 451 Take

New products, like new technologies, have short-term negative effects on the labor market; Amazon Go and autonomous vehicles will inevitably have a major impact on jobs, and it is likely that governments will have to pick up the pieces in the short term. However, automation of low-level, manual, physical processes has had an overall positive effect on society, and we expect such automation to continue to provide benefits. The ‘intelligence’ of computers (reflected in terms of algorithms, architectures and data) has effectively grown at a faster rate than the overall expansion of human knowledge over the past 30 years, and there is likely to be a point where computers can do many – or even a majority of jobs – cheaper and arguably better than humans. The number of jobs that are ‘easy’ for a computer to do has increased over the last decade ago, and this will continue.

The lasting effect of the Industrial Revolution was not that jobs were lost; it was that more jobs were created as a result of the huge increase in productivity. The advent of mills meant that hundreds of pieces of fabric could be made with the same amount of time and resources it previously took to make one. Greater productivity caused the price of textiles to come down, and demand soared. The general population benefited through steady wages and access to things they previously couldn’t afford.

This has been a recurring scenario in technology. For example, the mobile phones of the 1980s were expensive, bulky and only for the Wall Street elite. As time went on, processes improved, standards were set, and the price of mobile phones came down. Were jobs in cellphone factories lost as a result of improved manufacturing standards? No. Improved manufacturing triggered a ‘revolution’ of its own, and now nearly everyone has a mobile phone. This, in turn, has triggered the creation of new jobs through applications and other technologies based on mobile phones – all driven by the automation that made them inexpensive. The Luddites who campaigned against technology in the days of the Industrial Revolution were ultimately proved wrong.

The long-term benefit of technology is still a controversial subject. Yes, cellphones did create thousands of jobs, but what about the industries they destroyed? How about the jobs at traditional switched exchanges, for example? How many of those workers were able to repurpose their skills to the mobile sector? The issue is not a simple one.

As old technologies are replaced, skills are needed to support and develop the new technologies. However, it’s a slow process. Some historians believe that it took generations before the job-creating impact of the Industrial Revolution came to fruition. The Industrial Revolution did not take place over a few weeks; it took decades. Thousands of people working in craft industries saw demand decline for their homemade, more expensive products. Those who did not live close to mills often moved their families to completely different areas to compete with other people, who had also traveled miles, for the limited number of jobs. The mills could not scale quickly enough to replace the jobs they had destroyed, and people could not simply ‘reskill’ overnight – they had families to feed and possessed skills that had been handed down to them through generations.

It is generally accepted that automation causes short-term job losses; whether it also creates long-term job benefits is debatable. We, in the 21st Century, benefit in this regard from the internet. The internet offers users unprecedented access to learn new skills; it generally improves access to education, which means that those who are disintermediated as a result of technological change have a better chance of moving into a new line of work. In the mobile revolution, many people experienced in fixed-line or switching networks were able to apply their old skills to this new area, and shrewd companies invested in education so that they could create demand.

But it is not always so simple. Amazon Go is a prime example of a technology that could cause the layoffs of millions of people in one fell swoop. With Go, shoppers will no longer need to queue up to pay for goods – they just browse around the shop, pick up what they need and leave. The store is set up to detect what is in shoppers’ baskets and to automatically charge them and then send a receipt. Each year, users will save hours not standing in lines, and stores will save millions in payroll, which could result in lower prices. But what about the millions of people employed globally in the retail sector? Where will they go? Many of these workers are also the customers that will use the stores and bring in revenue. Of course, supermarkets will still need shelf-stockers, technicians and customer service reps – but will they move cashiers into these roles? To some degree, yes, but the lure of cheaper prices will mean a large percentage will likely be laid off.

The naive may say that Amazon Go will ‘liberate’ these workers, and new opportunities will be created for them. The optimistic will say workers could take the time to better themselves so they can handle more skilled jobs. But the reality is that these people have families, mortgages and commitments – even if they were able to retrain, who would pay for this education? How would they generate an income during this time? And perhaps more importantly, are there really millions of job vacancies waiting to be filled by former shop assistants? In decades, just like the Industrial Revolution, new jobs will be created in industries that are difficult to imagine now, and other sectors will counteract some of the loss in jobs in retail. But that will not happen overnight.

Of course an approach such as Amazon Go is not a panacea. Many families now do their food and household shopping using home delivery. Although robots are increasingly used to ‘pick’ the ordered items from stock for delivery, Amazon Prime Air and autonomous delivery vehicles are unlikely to replace the delivery person anytime soon. Finding the right delivery address, negotiating parking, loading and carrying the groceries, and dealing with replacements/returns/recycling still requires people.

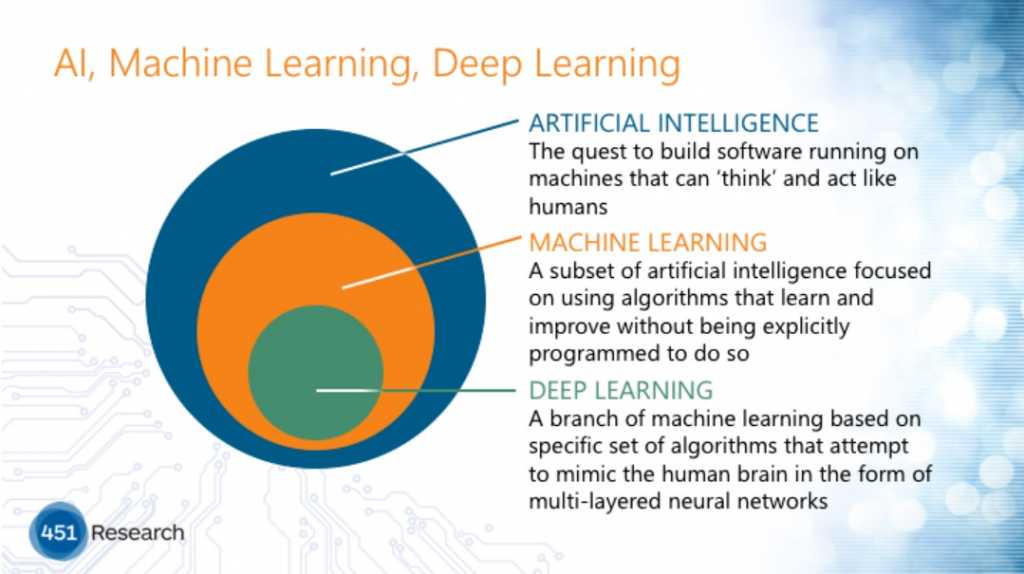

Machines have been gaining ground on humans in terms of their capability for work since Babbage proposed his ‘difference engine’ computer. But with the introduction of cloud computing, advanced technologies are now accessible to anyone with a credit card. Infrastructure seems old hat compared to the intelligence now on offer for dollars a minute from the likes of Google, IBM and Amazon. ‘Intelligence’ is the key term here – robots aren’t just better than humans at some physical tasks; they are creeping up on human’s cognitive functions as well. Deep learning, machine learning and AI are now powerful, accessible and relatively inexpensive.

Capitalism has enabled a constantly developing technological world. Capitalism relies on growth – continually striving to increase the GDP should ultimately mean greater goods, services and experiences for nearly everyone. (Can you imagine telling someone in 1917 that in a hundred years, people would be able to make a phone call to anyone in the world from their wrist?) The desire for profit creates innovation; innovation creates products that consumers want; improvements in efficiency lead to lower prices, followed by increased demand. This is a ‘compensation effect.’ Yes, automation decreases jobs in a specific industry, but it also creates new investments as a result of cost savings and increased profits. Automation can lead to wage increases as a result of greater profits. Prices are then likely to increase, and innovation directly leads to new products and new job opportunities.

So were the Luddites wrong? It’s not as simple as that. The Luddites’ worries were based on two key assumptions: First, that there is an finite amount of work to do, and if machines do the work, there is less left for humans to do. This is an incorrect assumption because as innovation occurs, new opportunities are invariably created. The second assumption is that machines do ‘easy’ work, and that the definition of ‘easy’ expands as IT progresses. This means the work beyond ‘easy’ requires greater brain power than a computer can deliver – creativity, insight, gut feeling, and multi-disciplinary talent and skills. With artificial intelligence, this balance of brain power is rapidly shifting. Artificial intelligence and the labor market is the subject of our follow-up report.